In December 2025, Reuters reported that China had successfully built a prototype Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machine inside a highly secure laboratory in Shenzhen. This machine represents a critically important strategic step, as EUV technology constitutes the cornerstone of advanced chip manufacturing at the 5nm or 3nm nodes and below—a technology that remains, to date, the exclusive monopoly of the Dutch company ASML.

Construction of this machine was completed in early 2025, and it is currently undergoing intensive testing, marking the first real challenge to the Dutch monopoly over this vital technology. This technology is considered the backbone of the advanced electronic chip industry required to power artificial intelligence applications, modern military systems, and smartphones.

Although the prototype has not yet produced commercial chips, the mere fact of its operation and generation of extreme ultraviolet light represents a massive leap in the timeline estimated by the West for China. While Western estimates predicted it would take decades, China aims to achieve this by 2028—a goal that now appears within reach following the operation of this prototype.

This Chinese prototype differs significantly in shape and size from its Dutch counterpart. While ASML’s advanced machine is roughly the size of a large school bus and weighs about 180 tons, the Chinese model extends to occupy nearly an entire factory floor. This immense size is attributed to the unavailability of the ultra-precise miniaturized components possessed by the West, compelling Chinese engineers to construct larger optical paths and power generators to achieve the same physical result.

Huawei is leading this massive project in coordination with the Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics (CIOMP), leveraging the extensive expertise of former engineers from the Dutch company who were recruited to work under a veil of total secrecy. The project relies heavily on the reverse engineering of older parts acquired from secondary markets, integrating them with local innovations.

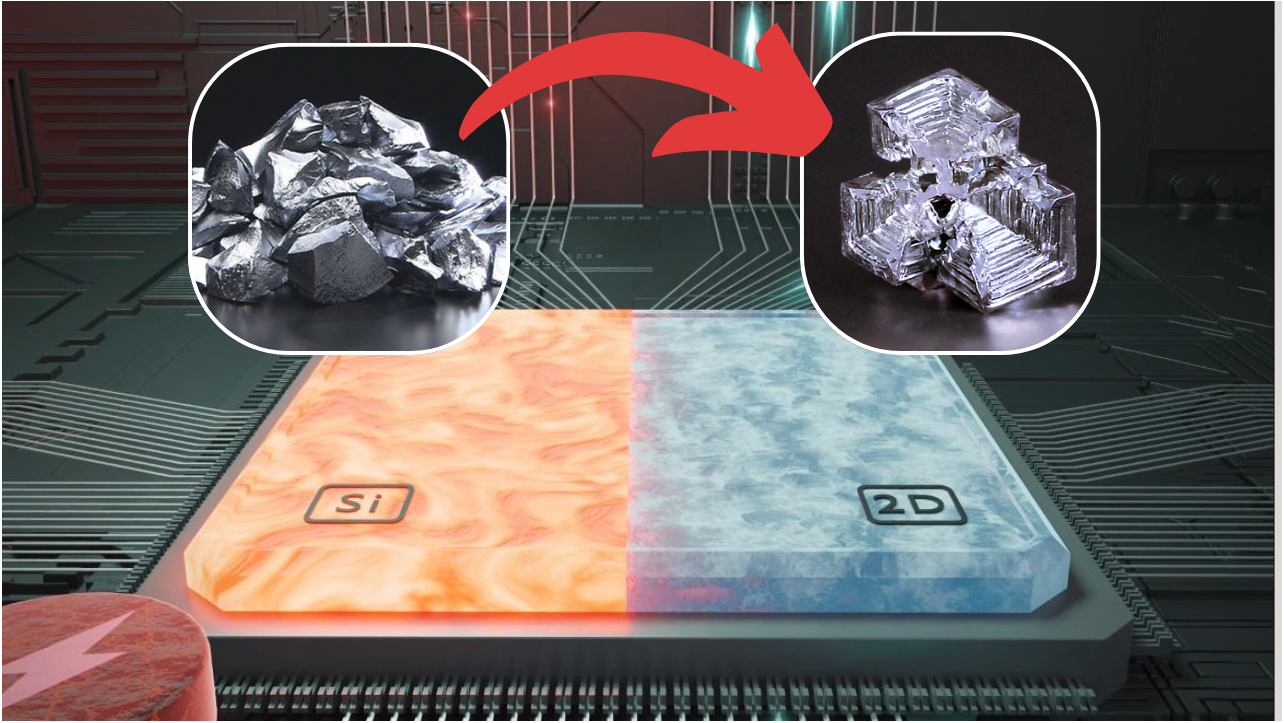

The paramount importance of this achievement lies in the vast difference between "Deep" Ultraviolet (DUV) technology—which China already possesses and manufactures through companies like SMEE—and the "Extreme" (EUV) technology it seeks. Traditional DUV machines operate at a wavelength of 193 nanometers and use an optical system based on glass lenses to focus light. This technology reached its physical limits at 7nm manufacturing precision and cannot economically etch the intricate circuits required for 5nm or 3nm chips. This highlights the necessity of transitioning to EUV, which operates at a precise wavelength of just 13.5 nanometers, allowing for the sculpting of billions of transistors in a space no larger than a fingernail—a feat impossible with previous-generation technologies.

The engineering complexity that renders the Dutch machine a technical marvel—with a price tag of around $250 million per unit—lies in how this light is manipulated. Extreme ultraviolet light is absorbed by any material it passes through, including glass and air; thus, the entire process must occur in a complete vacuum. Instead of lenses, the machine relies on a series of highly complex, multi-layered mirrors manufactured exclusively by the German company Zeiss. These mirrors are considered the flattest surfaces ever created by humans, reflecting and directing light with nanometric precision. The light source itself depends on bombarding molten tin droplets with high-power lasers 50,000 times per second, transforming them into plasma that radiates this rare light.

In contrast, China faced a formidable challenge due to the absence of Zeiss from its supply chain. This compelled the Changchun Institute of Optics to develop an alternative system for generating and directing light, believed to rely on high-discharge techniques or different light sources that require greater power and space, which explains the colossal size of the prototype. Although the Chinese machine is technically "rough" and lacks the precision of the German mirrors, it has succeeded in generating the required light, thereby solving the fundamental physical dilemma.

The Chinese plan aims to refine this prototype to achieve actual chip production by 2028 as an ambitious target, or 2030 as a realistic one, leveraging the fact that the theoretical science already exists and they are not starting from scratch.

By historical comparison, the Dutch company ASML took nearly two decades and billions of euros in research and development to transition from its first prototype in 2001 to widespread commercial production in 2019. China, meanwhile, is attempting to condense this timeline by mobilizing national resources and recruited expertise.

Nevertheless, the greatest challenge facing China remains not merely building a single functioning machine, but achieving yield rates that make chip manufacturing economically viable without causing chip contamination or damage—the stage that typically separates laboratory success from industrial success.